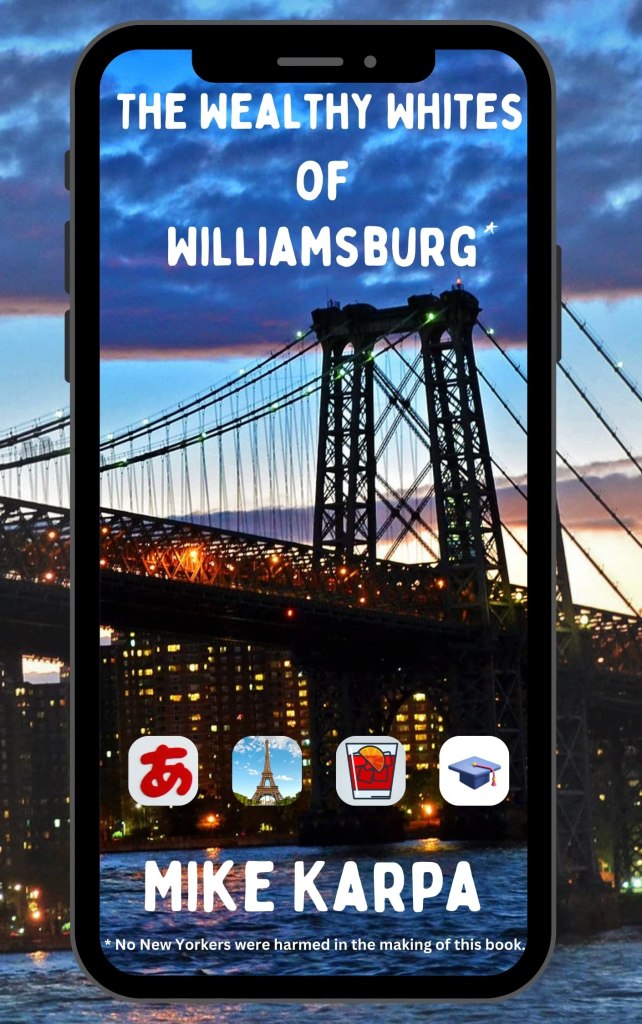

Mike Karpa wrote one of my favorite books from last year, and I knew I wanted to try more by him in 2026. Unfortunately, Red Dot is his only speculative fiction novel. I don’t read much non-Romance contemporary novels, but I chose The Wealthy Whites of Williamsburg as one of my 12 books to prioritize this year. The Wealthy Whites of Williamsburg won’t top my best-of lists, it solidified that Karpa is an author I will continue to read, and I desperately hope he’s got more stories in the works for the future.

Read if Looking For: insightful prose, dysfunctional families, insufferable lead characters, 5 year-olds obsessed with Lizzo

Avoid if Looking For: witty banter, fast-paced plots, diverse characters, endings as messy as the beginnings

Elevator Pitch

Casey and Roger are worried about making ends meet while living as lavish a life as possible. Roger is a former hit-screenwriter who now teaches Film courses at ritzy colleges. Casey runs a struggling localization business and is trying to get her daughter Abby into an exclusive elementary school. Demmy is Roger’s daughter from his first wife, who enjoys gossip and high school politics at her Japanese immersion school. Pretty much everyone has at least one secret (other than Abby, who just wants to watch Lizzo music videos), and nobody’s particularly happy with the state of their lives. You wouldn’t know it from the outside, however.

What Worked for Me:

Much of book was a triumphant success and showing vs telling. While showing isn’t inherently better (or worse) than telling, I’ve found in fantasy and science fiction, a lot of authors build theme through exposition and reflection. Here, Karpa took the opposite approach. Through the various family member’s eyes, he simply lets us into the lives of wealthy (but perhaps not rich), well-meaning, privileged folks. Demmy is consistently judging her parents for words and actions she views as socially unacceptable, yet in the same breath she makes worst-case assumptions about the black and brown people around her. Casey plays Lizzo for her five year old, but owns a car she can’t afford to impress the moms at a ritzy private elementary school. Roger confuses the names of Arab characters in his film class and overcorrects to try and prove he isn’t actually racist. It’s never preachy, rings true to reality, and is a fascinating dynamic to watch crash in slow motion.

Karpa also does a great job of tracing the commodification of queerness. Not from corporations, but as a level of status in some communities. As a teacher, it’s been fascinating to see how attitudes towards queer youth have shifted. Now, I teach in a liberal urban school and grew up in a rural farming town, but twenty years ago being identified as any letter of the alphabet wouldn’t have been desirable during your high school years. Demmy shares with her friends “I wanted to be Bi, but it’s just not happening,” which is followed by a round of debates on the merits of inventing queer relatives for Ivy League application essays. I love that kids in more and more places can explore their identities, and I also see a growing trend of mainstream queerness as a way to climb a cultural ladder. Of course, this has only been matched by the continued denigration of the more countercultural elements of our culture and history. Queerness wasn’t a major theme of the book (though Casey’s constant flirting with a hot mom was a prominent subplot), but as with Red Dot, I found a lot of interesting things about the queer experience in this book.

What Didn’t Work for Me:

I think Part 1 of this book was far more interesting than Part 2. The opening half was a collage of experiences; we flitted between family members, events, and relationship dynamics. While Karpa had a few major plot threads cooking, none could be called an ‘A Plot’. All of this went out the window in Part 2, which centered around the aftermath of a single disastrous day, mixed with one of the characters getting life-changing news. From here, the book became much more plot-driven, sacrificing it’s tight focus on exploring privilege. Even when Demmy interacts with a gay Arab man from France giving her advice on how to avoid the notice of authorities, that it didn’t feel like the same Demmy who was subconsciously passing judgement on Haitian immigrants. And unlike the messiness of Part 1, Part 2 resolved cleanly and brightly. Karpa was happy to brush off lingering plot threads, mend character dynamics overnight. It truly felt like I was reading a completely different book. Part 2 was the easier, quicker read, but it was certainly the less satisfying half of the story.

Conclusion: This book has a lot to say about privilege in America, but it didn’t quite stick the landing